Lori L. Tharps

Their mother was Eritrean and their father African American, but the two sisters, Lana and Asha, had vastly different experiences growing up mixed in Brooklyn in the 1980’s.

hen Asha was born, she was “the colour of milk,” Lana said. “When I was born, I looked like a chocolate drop.” As a teenager, Lana wished she had lighter skin, while her fairer sister had no idea of her longing.

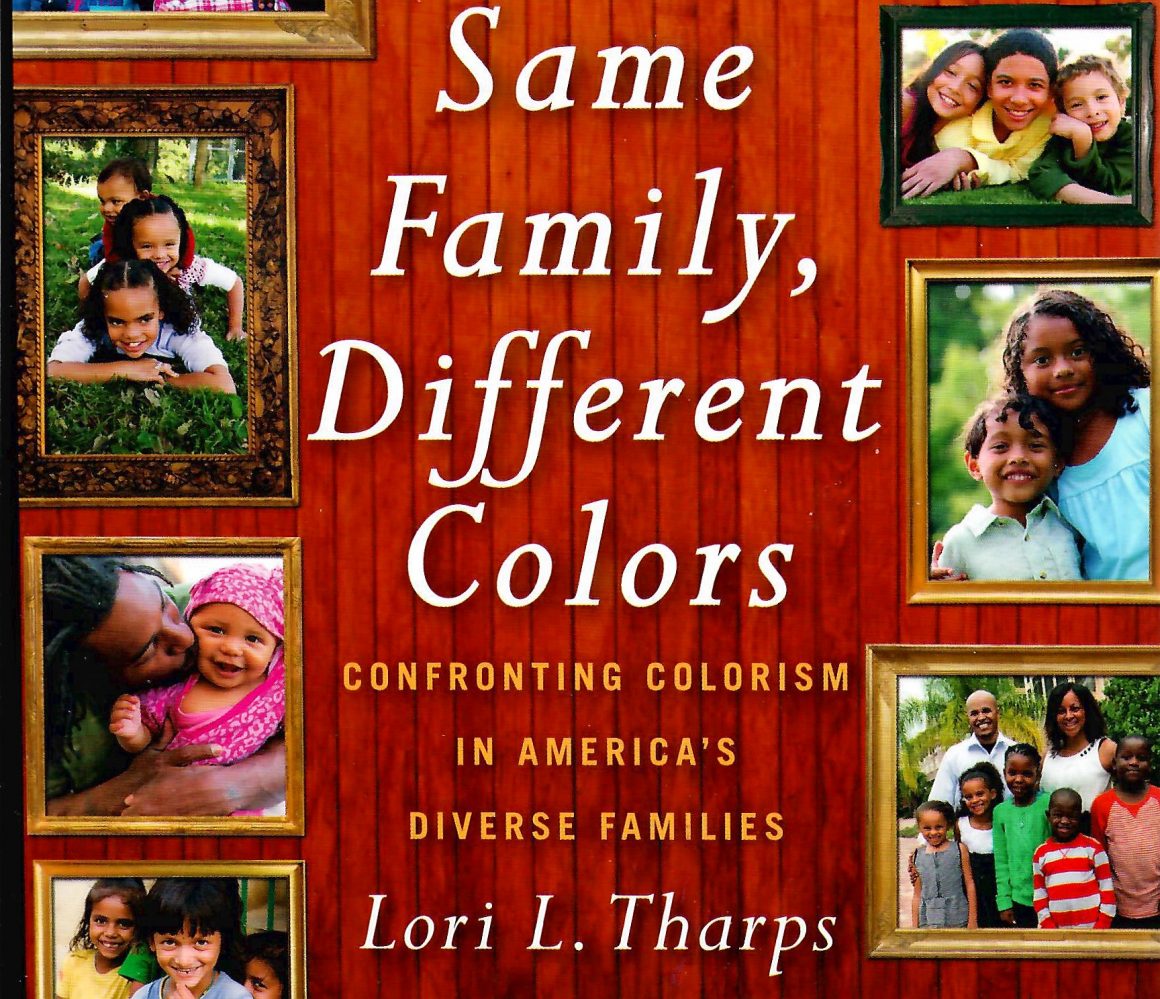

In her book “Same Family, Different Colours,” Lori L. Tharps explores the impact on families when members have varying shades of skin colour and the reaction in society when an individual has a darker, or unexpected, skin tone. Tharps argues that skin tone will become more important than race as America becomes less white and more multiracial as a result of mixed relationships and immigration. “Americans are on a collision course with a future in which the word ‘race’ gets redefined or perhaps even retired from official government use,” she writes. “In the meantime, skin colour will continue to serve as the most obvious criterion in determining how a person will be evaluated and judged.”

Tharps presents significant evidence that there are real-life ramifications to having darker skin. She cites a 2006 University of Georgia study that found that employers of any race “prefer light-skinned Black men to dark-skinned Black men regardless of their qualifications.” Economist Joni Hersch of Vanderbilt University Law School has found that immigrants with lighter skin earn between 8 and 15 percent more than similarly qualified immigrants with darker skin.

Tharps presents significant evidence that there are real-life ramifications to having darker skin. She cites a 2006 University of Georgia study that found that employers of any race “prefer light-skinned Black men to dark-skinned Black men regardless of their qualifications.” Economist Joni Hersch of Vanderbilt University Law School has found that immigrants with lighter skin earn between 8 and 15 percent more than similarly qualified immigrants with darker skin.

“Same Family, Different Colours” examines skin hue issues for African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans and mixed-race families, and probes the historical origins of a preference for lighter tones. In China, Japan and Korea, Tharps says, the desire for fairer skin was largely tied to notions of beauty and class. In the Philippines, light skin was associated with the power structure — that is, white colonizers and, later, the mixed-race mestizos. In India, Tharps notes that British colonization institutionalized the discrimination of people with darker skin.

Tharps delves into the family dynamics of different skin shades in an effort to understand how the issue plays out on the societal level. Does the experience within families point to the roots of pressures outside the home? Families want to match, she argues. “There’s something about the concept of family that demands a sense of uniformity, of sameness — same race, religion, class, and, yes, skin colour,” Tharps writes. It is a small step, she implies, from the family to society. “Skin colour matters because we are a visual species and we respond to one another based on the way we physically present,” she observes. “Add to that the ‘like belongs with like’ beliefs most people harbour, and the race-based prejudices human beings have attached to certain skin colours, and we come to present-day society, where skin colour becomes a loaded signifier of identity and value.”

While darker skin subjects people to discrimination, a lighter hue also can pose problems. Tharps recounts the experience of Enrique Martinez, a young medical student who was born in Mexico and spent his high school and college years in San Diego. “The first time I met Enrique I was shocked to discover he is Mexican,” Tharps writes. “Why? Because he has milky-white skin and thick, flaming red hair that hangs just below his shoulders.” Tharps reveals that meeting him forced her to “acknowledge how deeply ingrained stereotypes are, because even after learning of his heritage, I grappled with reconciling Enrique’s physical appearance with his Mexican identity.”

Enrique described his mother as Mediterranean white and his father and brother as brown with dark hair. While his parents never focused on the difference in skin colour between him and his brother, others couldn’t help noticing. People didn’t believe they were brothers. Enrique wasn’t even permitted to pick his brother up at school because the teacher didn’t believe that they were related. Enrique also found that his lighter skin gave him advantages in the United States denied to his darker father and b rother. When passing through border control on their trips from Mexico, the agents readily accepted his declaration of American citizenship but spent time questioning his father and brother. “This was when I started to realize that my skin colour in the United States was going to be very important in how people saw me,” Enrique said.

Enrique described his mother as Mediterranean white and his father and brother as brown with dark hair. While his parents never focused on the difference in skin colour between him and his brother, others couldn’t help noticing. People didn’t believe they were brothers. Enrique wasn’t even permitted to pick his brother up at school because the teacher didn’t believe that they were related. Enrique also found that his lighter skin gave him advantages in the United States denied to his darker father and b rother. When passing through border control on their trips from Mexico, the agents readily accepted his declaration of American citizenship but spent time questioning his father and brother. “This was when I started to realize that my skin colour in the United States was going to be very important in how people saw me,” Enrique said.

Author and journalist Sandra Guzmán (pictured below) was one of five children in a mixed Puerto Rican family; her father was black, and her mother had a Spanish heritage and a light complexion. “Guzmán described herself as having ‘African features, a flat nose, and curlier hair,’ ” Tharps writes. One of her sisters had blond hair, European features and their mother’s colouring, and that sister was favoured by both of their parents. Guzmán admitted to Tharps: “I always felt like if I were just a little blonder, if I just looked a little lighter skinned, maybe [my father] would love me more.” Her nose became her chief focus, and finally, just before she finished college, she saved up her money and got a nose job. Even with her new nose and straightened hair, Guzmán carried the wounds of her skin and her upbringing.

She understands that her parents are responding to social pressures that favour lighter skin; those demands affected her family’s life and ironically pushed her relatives to discriminate in ways they would condemn in others. “To grow up with a mother and an extended family that is so racist” Guzmán told Tharps, then stopped herself. “It’s not racist exactly; it’s just that they’ve been literally brainwashed to believe that they’re not beautiful.”

Dolen Perkins-Valdez

Jan. 27, 2017